Some may argue against contemporary criticism of Disney by saying it was of its time, or it was unconscious of its faults in gender representation or cultural appropriation. However, Bell argues that Disney's animation is not innocent; 'nothing accidental or serendipitous occurs in animation as each second of action on screen us rendered in twenty-four different still paintings' (108). With so much scrutiny over aesthetics and form, nothing is encoded into the text by chance.

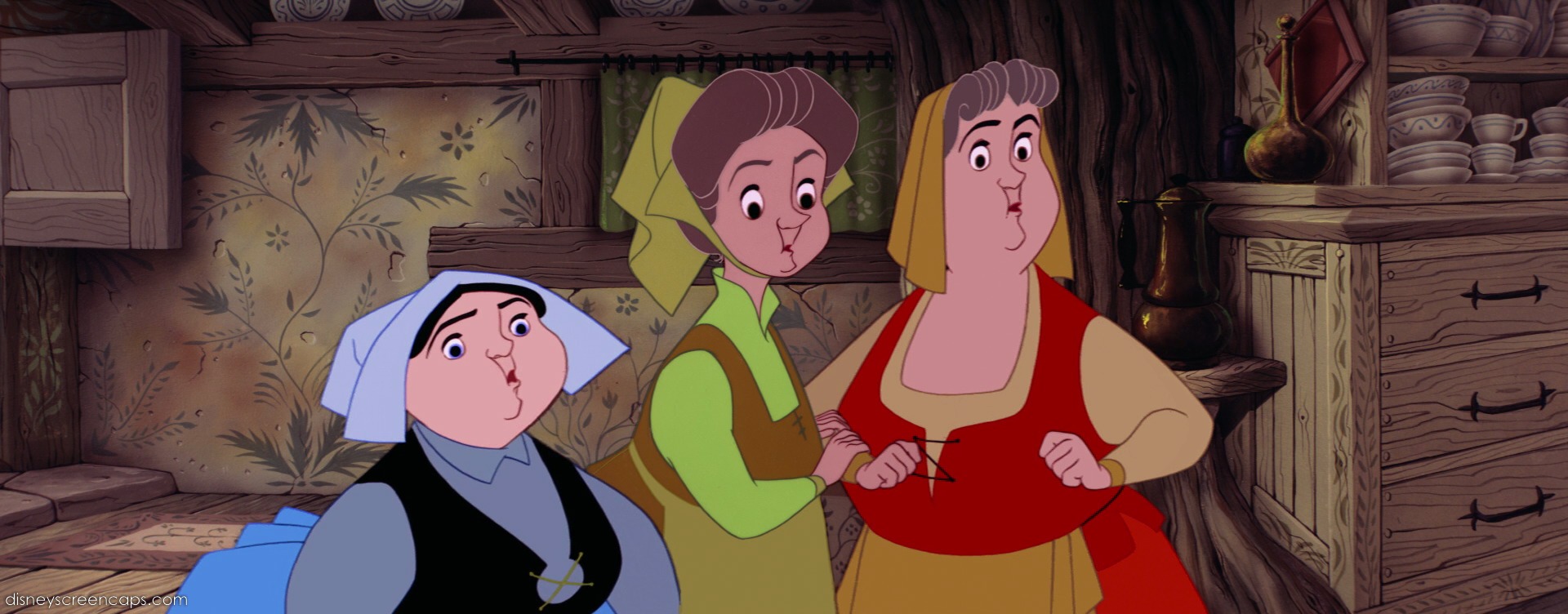

In this chapter, Bell divides representations of animated women into three sections, determined by the subject's stage of life. The age, and aging of women is a contentious issue, especially in male-constructed texts and discourse. 'The exacting, communally created images of women by men are consistently rendered in a somatic triumvirate of bodily forms and snapshots of the aging process. The teenaged heroine at the idealized height of puberty's graceful promenade;' 'female wickedness - embodied;' 'is rendered as middle-aged beauty at its peak of sexuality and authority' while finally 'nurturing is drawn in pear-shaped, old women past menopause [...] as the good fairies, godmothers, and servants' (108). We delve into inspection of how females in each of these sections are visually coded, betraying the intentions of representation by the animators: 'this essay explores the "semiotic layering" in the construction of women's bodies in Disney animation' (109).

The female characters in the folktale templates by the likes of the Grimms and Andersen are like 'painted ciphers' with no weight. However, with 'cinematic conventions of representing women, the levels become increasingly coded and complex. Disney's drawn women are transformed from weightless ciphers, drawn in black and white by men, into a second definition of cipher, texts encoded to conceal their meaning' (109) Ciphers of folktale heroines and female villains are transformed into 'conflicting codes of race, class and gendered performance' (110).

Firstly, Bell discusses the protagonists of many Disney fairy tale revivals - the heroines. Typically, 'Disney artists sketched the flesh and blood on these folktale templates with contemporaneous popular images of feminine beauty and youth, their sources ranging from the silent screen to glossy pin-ups' (109). The heroines are depicted as young, in their prime. These 'constructed bodies of young women' (110) have been produced under the male gaze. Animated heroines were 'both conforming to and perfecting Hollywood's beauty boundaries' (110). For source material, the animators looked at professional dancers' movements: 'their bodies built on the disciplined, expressive "naturalness" of dancers, have backbone' (112). This contrasts interestingly with the depiction, through their actions and discourse, that the heroines are usually seen as distressed damsels: spineless and unable to take care of themselves. 'While the characterizations of Disney heroines adhere to the fairy-tale templates of passivity and victimage, their bodies are portraits of strength, discipline, and control' (112). The juxtaposition of their aesthetic and their actions creates an interesting dynamic. 'The "backbone" of dance argues with the weakness of the narratized girls' (115).

These idealized young women have always been depicted in the male-dominated animation industry, in fact it wasn't until Beauty and the Beast that Disney had their 'first tale/film screenplay written by a woman' (114) The idea that women can produce more complex and nuanced female characters is a relatively contemporary notion. However, there is still a way to go in creating a positive, progressive medium for women creators and subjects in animation. Many of the tired tropes, such as the young, delicate heroine still exist, as is the rationale that they must find or marry a man to save them, and ultimately define them as characters. 'the tales still narrate and fulfill their destiny as marriage/reward for the prince/beast; their commodification in the marriage plot' (114). The heroines are desirable creatures, worthy of being rescued/saved and 'won.'

'The young heroines are typical of "the perfect girl" whose body, voice, and destiny are a "mesmerizing presence" through which "girls [enter] the world of the local hero legend, and experience the imposition of a framework which seemingly comes out of nowhere - a worldview superimposed on girls but grounded in the psychology of men"' (121).

|

| Ariel in The Little Mermaid source: http://princess.disney.com/ariel |

|

| Aurora from Sleeping Beauty source: http://m.niusnews.com/upload/imgs/default/intern/bo0430/Walt.jpg |

These women have 'power and authority as femmes fatales, living and thinking only for themselves as sexual subjects, not sexual objects' (116). By depicting evil women in a sexualized, wanton light, the animators manage to 'subvert their authority even while fetishizing it - these deadly women are also doomed women' (116). Unlike the innocent, 'good' coding of the sexually mature heroines, these slightly older women are vilified for taking control of their sexuality, and being seen to 'flaunt' it, which is not approved of in the patriarchal society. Therefore, they must be punished. 'Their excess of sexuality and agency is drawn as evil' (117). In contrast to the younger heroines, 'congruous cinematic codes inscribe middle age as a time of treachery, consumption, and danger in the feminine life cycle' (116). The wicked women harbor depths of power that are ultimately unknowable but bespeak a cultural trepidation for unchecked femininity' (121). Interesting to note, it is these villainous women who are the only characters to address the audience/ camera/ screen directly out of all the women.

Animators designed these body types as symbolic of predatory animals. 'The construction of their bodies on predatory animals heightens the dangerous consumptive powers of the femme fatale' (117). For example, Maleficent was designed like a giant vampire bat. 'Disney's famous decree for Snow White's Wicked Queen, that she be a "mixture of Lady Macbeth and the big bad wolf"' (117). Ursula has 'consumptive, deadly' octopus tentacles (117). All the above emphasize unsubtley 'the potency of women's evil and their dangerous and carnivorous threats to order' (117). The last point made by Bell I find to be the most interesting, and perhaps, 'telling' one. Disney of course, comes from a time when American capitalism was coming into its own - when small media houses and studios were spreading into large national corporations and conglomerates. It was a time of the market and when the ultimate success was seen as being a productive, financially useful part of society. Men worked; produced goods and services and brought home money. Women provided for their families by raising children and completing all the menial household tasks. That was a woman's ultimate contribution to society, to be a good mother and wife. In this way,, Disney manages to vilify the antagonists in an even more insidious way. ball states ''it is appropriate that the femme fatale is represented as the antithesis of the maternal - sterile or barren, she produces nothing in a society which fetishizes production' (119). She was undesireable in Disney's ideal world.

|

| Ursula from The Little Mermaid source: http://seriable.com/upon-time-season-4-alias-star-play-ursula/ |

|

| Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty source: http://linksservice.com/disney-sleeping-beauty-maleficent/ |

|

| Fairy Godmother from Cinderella source: http://disney.wikia.com/wiki/File:Fairy-Godmother.png |

|

| The fairies in Sleeping Beauty source: http://disney.wikia.com/wiki/Flora,_Fauna_and_Merryweather |